The Journey of US Secretary of Defence’s son in search of truth and reconciliation

March, the Central Highlands. A salt-and-pepper haired American man stands silently in the Ia Drang Valley at the foot of Chu Prong Mountain (Gia Lai). Before him stretched an ancient emerald-green forest, but sixty years ago, this was a fierce battlefield. The elderly veteran accompanying him quietly says: “Nearly two hundred of my comrades fell here.” He bows his head, lays a bouquet of yellow chrysanthemums against a tree trunk, sticks a burning incense coil into the red earth, and begins to weep.

This man is Craig McNamara, son of US Secretary of Defence Robert McNamara, who is on a personal quest for truth and answers about a war that ended more than half a century ago.

Robert McNamara — the “chief architect” of America’s War in Vietnam — once believed that ramping up troops and adopting a “search-and-destroy” strategy could bring victory. But as the forests were ravaged by napalm bombs and Agent Orange, and American casualty counts climbed, doubt slowly crept into his mind. In the end, he was forced to admit that this war was “a terrible mistake.”

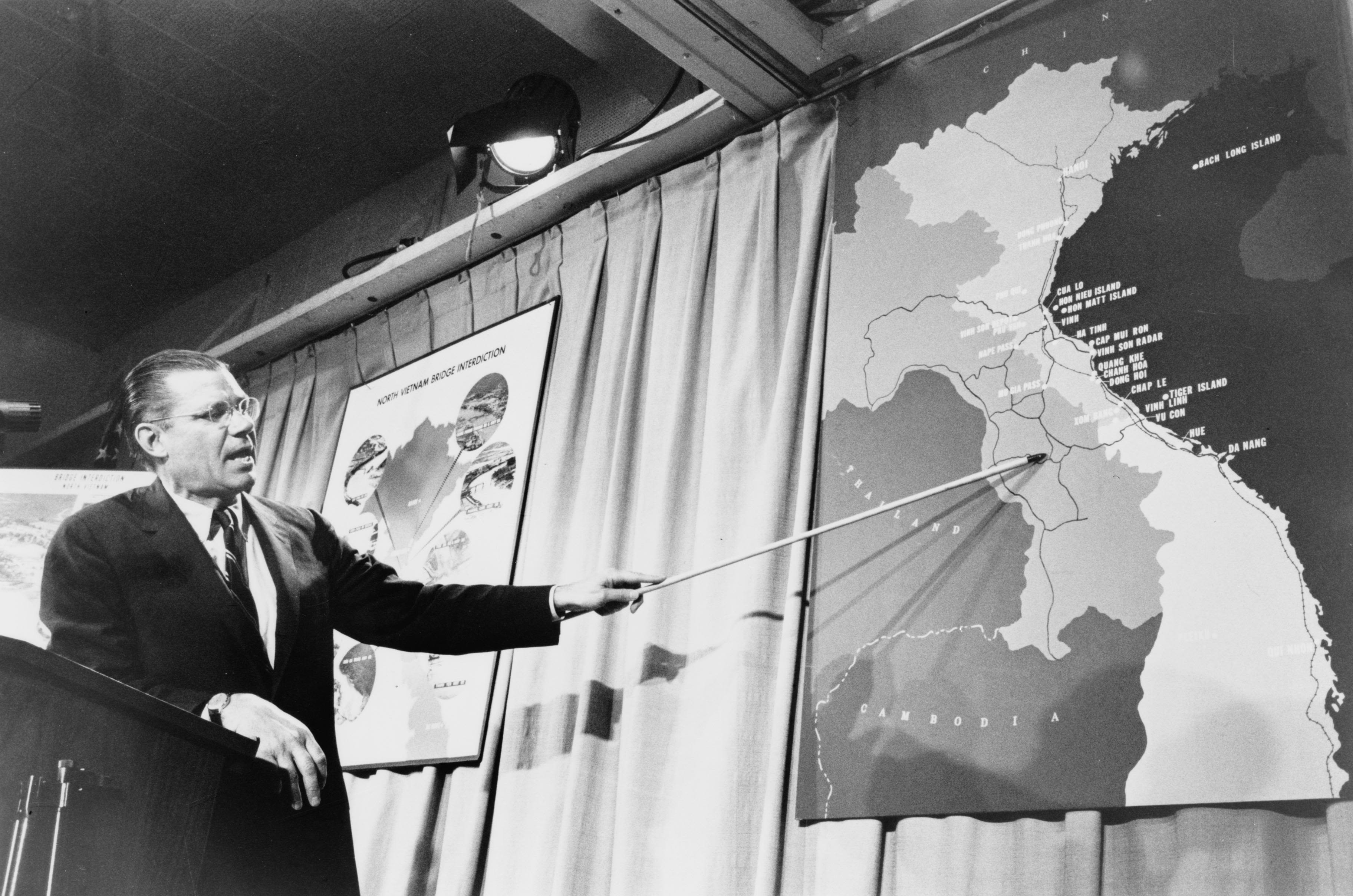

Secretary McNamara in a meeting on the Vietnam war. (Source: Wikimedia)

Secretary McNamara in a meeting on the Vietnam war. (Source: Wikimedia)

In 1965, Craig, then fifteen, stood among the crowd of protesters against the Vietnam War. At the very same time, at the Pentagon, his father was shaping military strategies to expand the war. Craig could never have imagined that decades later he would set foot on these historic battlefields, where his father once ordered bombings, erected electronic fences, and deployed Agent Orange. He was not a soldier, yet his life has been bound up by this war in its own unique way.

“When I was ten, my family moved to Washington, D.C. By the time I was fifteen, I was boarding at school. Back then, I didn’t really understand much about the Vietnam War,” Craig recalls.

Until one day, he attended a seminar on the Vietnam War. A professor from Dartmouth College spoke about Vietnamese history and culture, about the aspiration for reunification of a people who had endured thousands of years of wars to defend their homeland. He argued that US involvement in the war was not only wrong, it was based on misinformation. Craig was stunned to realise that what his father and the US Government had said about the war wasn’t true.

From then on, conversations between Craig and his father became tense. He asked many questions about America’s war in Vietnam but received no answers from his father. There seemed to be an invisible wall between them. His father left the Pentagon when he was 17. But it wasn’t until he turned 18 that he truly joined the anti-war movement.

Craig could never have imagined that, decades later, he would set foot on the very battlefields where his father had once authorised bombings, electronic fencing, and the use of Agent Orange. He wasn’t a soldier, but his life remained entangled with that war in his own way.

After leaving Stanford University, Craig spent several years travelling around South America, working on farms, before graduating from the University of California, Davis with a bachelor’s degree in soil science. He became an organic farmer, hoping to contribute to a more sustainable food system. Yet the war in Vietnam continued to haunt him.

In 1995, he wished to accompany his father to Hanoi to meet General Vo Nguyen Giap, but Robert McNamara declined.

“I believe that had he encouraged me to join him in his meeting with General Giap that I might have been able to encourage him to apologise for his decision to escalate the war and help him move forward by offering significant reparations to soldiers and families in both the US and Vietnam whose lives have been forever changed by the war.”- Craig said.

Craig with the walnut crop. Photo courtesy of Craig

Craig with the walnut crop. Photo courtesy of Craig

Craig first came to Vietnam in 2017 with his daughter Emily. They travelled across the country, learning about the history, culture and people, developing a deep relationship with Vietnam. In early March 2025, he returned to make the documentary “The Clash of Wills” to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Liberation of the South of Vietnam, at the invitation of VTV4.

On the historic Ia Drang battlefield, where the first major battle between the US Army and the Liberation Army took place in 1965, Craig walked with two veterans of the 66th Regiment, witnessing with their own eyes the traces left by the war. More than 1,000 US soldiers and 900 Republic of Vietnam soldiers fought with more than 2,000 Liberation Army soldiers for four days, starting on November 14, 1965. The two sides fought fiercely at close range, “hitting each other’s waists”.

On the McNamara fence. Photo courtesy of Craig

On the McNamara fence. Photo courtesy of Craig

I believe that had he encouraged me to join him in his meeting with General Giap that I might have been able to encourage him to apologise for his decision to escalate the war and help him move forward by offering significant reparations to soldiers and families in both the US and Vietnam whose lives have been forever changed by the war.

This was the first time in more than 60 years that two veterans, Nguyen Van Lung and Pham Van Dac, had returned to where they had lost hundreds of comrades. As they walked on that red soil, their bodies trembled, and sobs burst from their chests. The painful memories of their fallen comrades flooded their minds. Craig hugged them tightly, crying together.

“We can forgive, but we will never forget,” said veteran Van Lung. Craig realised that, for them, the past could be left behind, but the lessons of war must be remembered so as not to repeat mistakes.

When embracing his journey to Vietnam, Craig carried the flag of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam — which had been given to his father as a relic of the battle after being taken from a dead North Vietnamese soldier.

The flag, which had hung on his bedroom wall, was returned to Lung and Duc to commemorate this tragic scene. The four of them together spread out the flag. Three soldiers trembled with emotion as they recognised the dried bloodstain of their comrade still intact, in the corner of the flag clearly marked with the inscription: “17 - 11 - 1965."

“We walked hand in hand. They wanted me to know that as hateful as this war was, that they had forgiven their US counterparts and have spent the rest of their lives wanting peace between our nations,” Craig said.

Craig visited Khe Sanh, Truong Son Cemetery, Ta Con Airport, Hien Luong Bridge (Quang Tri Province), Son My Commune (Quang Ngai Province). He also visited My Tho in Tien Giang Province where the Ap Bac battle took place.

For him, this trip has put in place the missing pieces of the Vietnam War. From the 1963 battle at Ap Bac, where out-manned, out-gunned, and under-supplied North Vietnamese soldiers demonstrated that they could fight and significantly damage the best equipped Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) troops and US advisors, to the first major battle between the opposing sides in 1965 battle at Ia Drang. In Ia Drang Valley two North Vietnamese regiments engaged the First Calvary Division and First Battalion of the Seventh Calvary in fierce fighting amid difficult terrain.

“My recent trip to Vietnam illuminated for the first time that the year 1965 was what I will call; The beginning of the end. By that I mean that it was the year that my father realized that the war could not be won by the U.S,” Craig shared.

Robert McNamara also grappled with his decisions. In his memoir “In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam”, he presented 11 lessons derived from his experience at war. But Craig believes that if he had followed those lessons, the US would never have entered into the Vietnam war.

At the Truong Son National Cemetery, Craig bowed his head and lit incense at rows upon rows of graves stretching far into the distance. Before him lay thousands of Vietnamese soldiers who had passed away in their youth, taking with them dreams and aspirations never fulfilled. He stopped at an unmarked grave, stunned by the inscription on the headstone: Born in 1950. Died in April 1968. At that moment, he could not hold back his tears. “The soldier and I were both born in 1950 and he died in April 1968, the year that we both turned 18 years old,” said Crag.

Craig McNamara at the Truong Son National Cemetery (Quang Tri). Photo courtersy of Craig McNamara

Craig McNamara at the Truong Son National Cemetery (Quang Tri). Photo courtersy of Craig McNamara

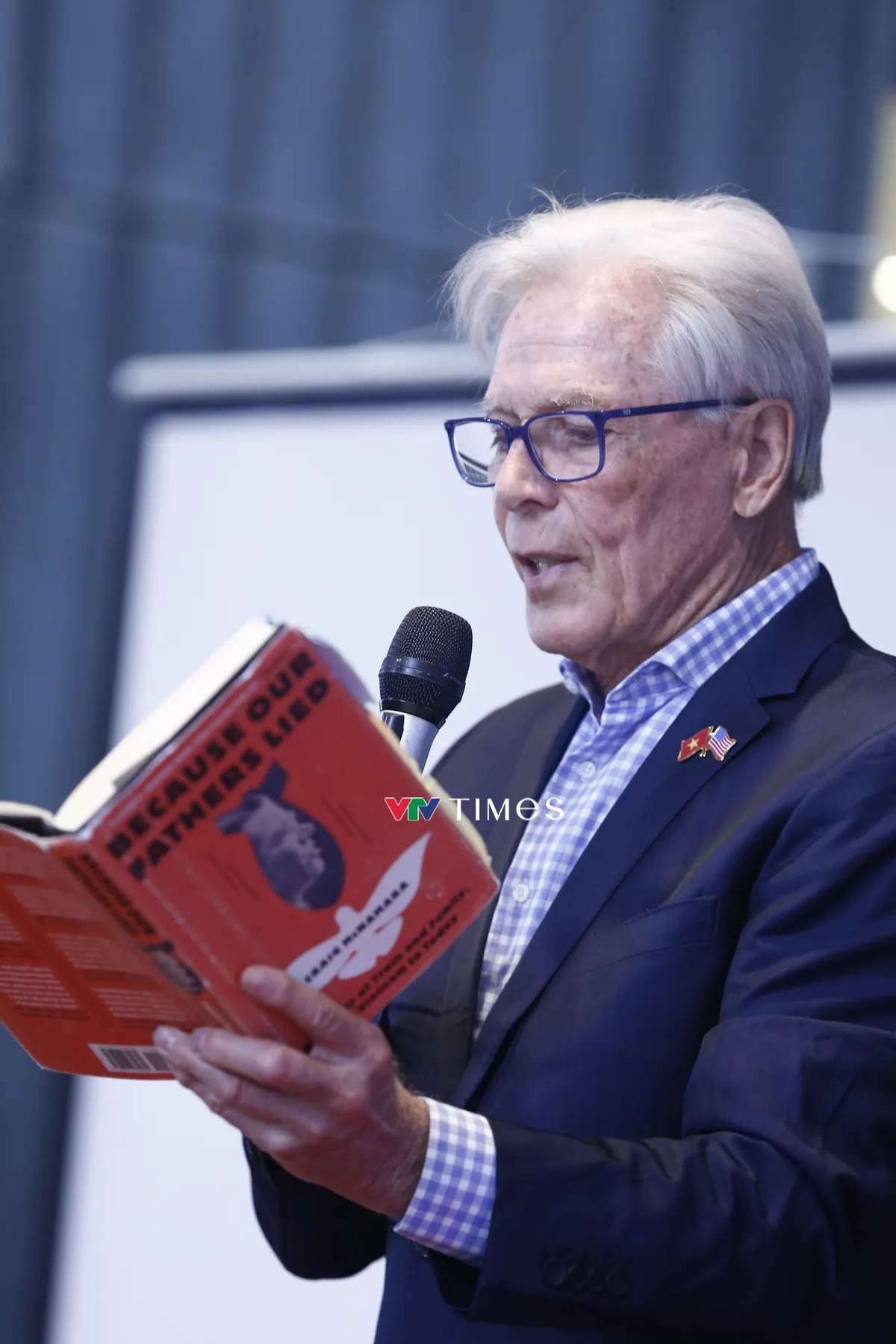

During this trip, he also introduced his memoir “Because Our Fathers Lied: A Memoir of Truth and Family, from Vietnam to Today” at the Vietnam Military History Museum. The book recounts what he has experienced, what he learned from his father, and what he hopes future generations will understand. He hoped that history will not be forgotten—and more importantly, that its mistakes will never be repeated.

“What I hoped to accomplish in writing my memoir was to unpack my relationship with a very loving and kind father. I wanted to better understand how a remarkable human being, a man of integrity, could make decisions that led to the destruction and deaths of millions of people”, he said.

Photo: VTV

Photo: VTV

Craig also noted that he plans to continue his efforts to promote peace and mutual understanding between the two countries. He expressed his belief that VTV4's documentary series will serve as a wonderful bridge in this mission. I will also continue to cooperate with Project RENEW to support the clearance of unexploded ordnance and address the consequences of Agent Orange/dioxin.

Craig McNamara set out in search of the truth, but along the way, he discovered something even greater. He came to understand that war is not just numbers on a map or strategies discussed in boardrooms, it is the irreparable loss endured by millions of people. And the only thing that could be done was to ensure that the same mistakes never over and over again.

Photo 1: Craig McNamara (right) and veteran-writer Van Lung. Photo 2: Craig McNamara (third from left) and veterans who took part in the Plei Me – Ia Drang Campaign. Photo 3: Craig McNamara (right) and veteran Pham Van Dac at the historic Central Highlands battlefield. Photo courtesy of Craig.

Photo 1: Craig McNamara (right) and veteran-writer Van Lung. Photo 2: Craig McNamara (third from left) and veterans who took part in the Plei Me – Ia Drang Campaign. Photo 3: Craig McNamara (right) and veteran Pham Van Dac at the historic Central Highlands battlefield. Photo courtesy of Craig.

E-Magazine | Nhandan.vn

Content: ANH THO

Translation: NDO

Design: NDO